Next December, La casa de papel will end for the second time. Its first final was broadcast on November 23, 2017 on Antena 3. It started at 10:53 p.m. The robbery of The Professor (Álvaro Morte) and his henchmen at the Currency and Stamp Factory, which had started with 4.5 million viewers, ended 15 episodes later, having lost half of that audience along the way. “The series was closed. It ended when they considered it had to end, ”says Jaime Lorente (Murcia, 29 years old), the actor who plays Denver, the coolest thief in a gang that is already quite badass. "It started with a large audience because it premiered after a Champions League match, a Madrid-Atleti match," adds Miguel Herrán (Málaga, 25 years old, Rio in the series). "Then it went down, but that's normal in any Spanish series." What is not normal is everything that happened next.

The fifth and (this time) final season of La casa de papel has started on September 3 with a batch of five episodes. The series, which recounts the spectacular robberies of a gang of thieves against multimillion-dollar institutions (never individuals), says goodbye in a world completely different from the one in which it was born, not only because of the pandemic but because Netflix, the platform that resurrected, has changed the rules of the audiovisual industry. Today it is the fourth most viewed fiction in its catalogue, to which more than 208 million subscribers in 190 countries have access.

If this last season comes in two batches, it is because, when they published the trailer in the spring, most users on social networks assumed that its premiere was imminent. Netflix decided to advance the release of the first half. After all, the phenomenon of La casa de papel began with a popular outcry. After its broadcast on Antena 3, Netflix included it in its catalog through the back door and its popularity grew exclusively thanks to the fact that users recommended it. On April 17, 2018, the platform announced that it was the most watched non-English speaking series among its titles. The next day, he announced that La casa de papel would continue on Netflix. The perfect symbol of the new audiovisual ecosystem.

Lorente perfectly remembers the first time he became aware of the fervor that the series aroused outside of Spain. He had to go to a Netflix event in Rome, but when Elite was filming he arrived later than his companions and none of them warned him that there were thousands of people waiting for him alone. “I opened the car door, the security guys grabbed me by the armpits and swept me away like a little fish,” he recalls. Miguel Herrán remembers another time in Sardinia: “They took us out of the hotels, people chased us down the street, others stood on the roads with flags to greet us. We rented a boat and people chased us with yachts, when we stopped they came swimming and got on our boat. We stayed locked up in a restaurant, the police had to come to evict the town”.

In a matter of weeks, a cast that, at the beginning, if it attracted attention for anything, was precisely because of the absence of stars (except perhaps Úrsula Corberó and Alba Flores), had become famous in 190 countries. Jaime Lorente was just someone among the Spanish after-dinner audience (his only experience of him had been several episodes of El secreto de Puente Viejo in 2016) when, overnight, people began to imitate him on the street. They imitated Denver, of course, because the only thing Jaime is gross about is his jaw: he has published a book of poetry (Apropos of your mouth, edited by Espasa is Poetry), he spent his confinement reading Lorca for his 14 million followers on Instagram and has been open about depression and anxiety. After making his film debut under the command of one of the most respected filmmakers in the world, Asghar Farhadi, in Todos lo saber (2018), Lorente has headed the most expensive Spanish series in history, Cid (Amazon Prime Video). And although it may seem contradictory to reject fame and continue getting involved in ambitious projects, he trusts that the more roles he plays, the less people will pay attention to him.

Whatever he does, it will be in Spain. "I don't want to leave, why would I want to leave? We do shitty things, we live in a shitty country and right now we have a kind of responsibility. My country has given me a lot,” he says. Herrán agrees: “As a Spanish actor I want to bet on my country's industry. I mean, you give me success and I take and leave with him? They have offered me to go to Miami to shoot and as soon as a movie came up I stayed here. If I can choose, I stay here."

Miguel Herrán was found by Daniel Guzmán on the street (literally) and offered a role in his directorial debut. In exchange for nothing (2015) he gave them each a Goya and at the age of 20, for the first time in his life, Herrán found a direction: he left behind the street life and focused on working on a career as an actor. The paper house precipitated events and he was dislocated. “When a project came to you, it was clear to you that they had taken you for your talent, you trusted more in yourself and in your tools. Now I always doubt if they catch me because of me or because of the image that is being sold from La casa de papel”, he confesses. The first thing he did when he met the director of his next film was to ask him why he had signed him. "Because you did the best casting," he replied. It was one of the best moments of his life.

Like his partner Lorente and other artists of his generation, Herrán has naturally approached his mental health problems. If with the confinement Lorente discovered that he did not know what his own hobbies were, Herrán saw that he was not capable of enjoying the moment because he was always thinking about the next thing. Anxiety, entangled with a vigorexia that he suffered in adolescence and whose ghost never completely disappears, has caused him a suffering that he prefers to explain: “Of all the people who approach you, very few ask how you are, they assume that you are motherfucker because you're famous."

Ironically, fame is the Achilles' heel of these two stratospherically well-known men. While they were still learning how to manage it, Herrán and Lorente appeared on Elite in 2018, another Netflix worldwide success that caused a curious statistic: Herrán became the fourth star of the platform that had gained the most followers on Instagram in 2018, Lorente was the fifth and María Pedraza, also an interpreter in both series, the sixth. "Sometimes I have had the feeling of being a Netflix actor," confesses Herrán. The influence of the platform is such that it has changed even the meaning of the colors: the other day Lorente went to the theater, the stage lit up red at the beginning of the play and he thought: “Netflix”. “You just won a Goya [as a revelation actor in 2016, for In exchange for nothing] but they take you out of Spanish cinema and suddenly you are a Netflix actor who is going to do this and that. Even the movie I starred in, Hasta el cielo (2020), has been on Netflix too." The platform has announced that it will adapt Hasta el cielo to the series format. Miguel Herrán will not participate in it.

The paper house was from the beginning such an exportable product—the Dalí masks worn by robbers, their aliases of international cities, the Hollywood rhythm of the narrative—that it almost seems as if they had it all planned. Except that if they had planned it, it wouldn't have gone so well: there are shots that have to be improvised on the fly. The justice aspect of the argument, like Robin Hood, Ocean's Eleven or Snatch, pigs and diamonds, caused the first readings of the phenomenon to be political. “The series winks at the historical moment we are living in, in which we all feel like victims of a system that would only want our poverty”, analyzed Il Corriere della Sera. “An incitement to rebellion?” asked Le Monde. The former mayor of Ankara asked the secret services to intervene in this "very dangerous symbol of rebellion". Dalí masks proliferated in the protesters against the Macri government in Argentina, in the banknotes launched by Uruguayan anti-establishment artists and in the Rio de Janeiro carnival. "The original name was going to be Los desahuciados, because it spoke of people who were evicted and through [this robbery] they were looking for a new life," says Lorente.

But the dimension of the phenomenon ended up dispelling any sociopolitical reading. That resounding debut thanks to Madrid-Atleti in the Champions League was no accident: the potential audience for this series is the same as for football, that is, practically anyone. His fans include Neymar, Romeo Santos, Chiara Ferragni, most likely ourselves and a good part of our family members. The popularity of La casa de papel has benefited from its forceful simplicity: La casa de papel is exactly the series that it seems, one in which the leader of the gang uses expressions such as "let's mess it up brown" and in which the coffin from Nairobi (Alba Flores), murdered last season, had “la puta ama” written on it. A series that has inspired the largest escape room in Europe.

His feat has been treated in the same terms as that of a humble football team that nobody sees coming (Depor of the centenary, Ranieri's Leicester in 2016), whose fans also support through badges, chants, tattoos and even a certain connection identity. There is a national pride towards the triumph of La casa de papel only comparable to that awakened by Nadal, Gasol or Belmonte. "It's that it has the same elements as a football club," says Jaime Lorente. "There is a coach, some players, a kit, an anthem, a color and some tactics."

When the third season of La casa de papel, the first on Netflix, was broadcast, there was more talk about its international impact than about the characters. Nobody cared what La casa de papel meant. The colors are above their players: the star of La casa de papel is La casa de papel. “You are a kind of souvenir. And very cheap ”, indicates Lorente regarding his role as a piece of the enormous gear. “You buy something in the supermarket and you want what is inside the box. Success is more difficult to manage than failure, because failure is forgotten but success cannot be taken away even with turpentine”.

According to Miguel Herrán, some other colleague "went a little crazy" with the worldwide hit. "It's that you can be an actor who doesn't like fame or you can be an actor who does like it," says Lorente. “And if you like it and something like this happens to you, there is a 99% chance that you will end up becoming an asshole.” Both agree that those who do not like fame, as is their case, are very likely to "end up sad" and consider leaving the interpretation. “I love my job but I don't like so much exposure. Suddenly I go down the street and they shout at me 'Rio!' and they joke at me. That's what I hate the most, being treated like a dog: 'Hey you, Rio!' They don't value your work or your performance."

In accordance with the canons of Hollywood, by which La casa de papel is governed, each new installment cannot be limited to continuing the story. It has to be bigger than the previous one. From shooting in Colmenar Viejo (Madrid) they went on to do it in Thailand or Italy. The creator of the series, Álex Pina, admitted in an interview with EL PAÍS in 2020 that when it came to facing his debut on Netflix, they were overwhelmed by a panic of empty spaces. “We were freaked out. We told ourselves: 'I don't know if this is good or not, but don't let it get boring'. After their move to Netflix, the muggers stopped having conversations around tables full of bottles of Natural Honey shampoo, but otherwise got caught up in a constant "no balls." Of course, it is precisely that vocation to shock, to reach the next climax as soon as possible and to be a freak, what arouses the euphoria of his fans.

"It's that the premise of La casa de papel was already very extreme, if you accept that, anything can fit in," explains Lorente. "The intention was always to make a great entertainment to see with popcorn and coke, not to spark a revolution in Brazil." Herrán thinks that, as the screens have become smaller, it is the industry that has become too big: “There is too much consumption, there is too much supply and you have to distinguish yourself in something. And what are you doing? Take it all to the extreme. The perfect example is Elite, I haven't seen it but everyone is telling me that this season is outrageous, that they have gone too far... But of course, if not, you have 10,000 identical products”.

Lorente acknowledges that there are times when he has felt that so much noise suffocated what really hooked the public: his characters. “There are seasons for me when things that should be resolved through conversation were resolved in half a second or with a glance,” he laments. "Yes, but I don't like it either when in a movie they are in a fucking robbery with seven bombs and everything stops to hug the girl while the kidnapper is unconscious and gives him time to get up," Herrán counters. “That doesn't happen here: the frenzy doesn't give you time to do absolutely anything, but the viewer isn't going to notice it either. He is going to notice the bomb, the look and when he wants to realize the series is over. In fact, I think that many people while watching series are looking for things on their mobile phones about the series, its actors...”.

The series has applied that you have to leave the party while it's still fun. But he is going to do it by blowing everything up: his last season is a war blockbuster that towards the end will pick up the pieces and focus again on his characters. So much war has left the actors with a certain post-traumatic syndrome and when describing the filming of these last 10 episodes, Herrán involuntarily evokes Colonel Kurtz from Apocalypse Now: “Infinite... infinite...”.

"I've been shooting all 10 episodes, man," says Lorente. “Three weeks with a sequence in a kitchen that will then last three or five minutes. All days the same. What happens to my character is, I think, the strongest thing that has happened to anyone in the series, a very complicated emotional and physically scene, the fucking war. There would come a point where he would pick me up and hear: 'Again...Again!'

Miguel Herran. I've been throwing a grenade for three weeks. It's exhausting because I like to interpret.

James Lorente. That is. And there are days when you don't feel like an actor.

MH Sure, you think, fuck, I'm a well-paid helper. I'm here without saying anything, without doing anything, without feeling anything, with the camera so fucked up that I don't know if I'm really being seen. Spending all my fucking energy to do the best I can. And there comes a moment of desperation in the second week when you say, 'look man, I can't take it anymore'. And then they tell you to hold on a bit, then your short [shot] arrives. And you answer: 'Sure, but why didn't you do it a week ago?'

JL Now you are empty.

MH You are completely empty.

And don't you feel like a kid playing shoot-em-up?

MH In fact, it is not enjoyed. Think that it is a weapon that weighs three and a half kilos, that you are pretending all the time because it does not really shoot. And you don't see anything.

JL The dust gets in your eyes, you cough, the effects guy loses his grip and something explodes in your face.

MH You have a firecracker here, a splinter pops out...

JL It's that you're scared sometimes. Do you remember that bottle that was behind you? It's dangerous man, it's dangerous.

MH And the firecracker that they put you here? [points to arm]

JL Yes, yes, he blew me up in a shot.

Could it be said then that they wanted to finish?

JL Yes, because the intensity that one experiences in the filming of La casa de papel is very strong. It's a 10 hour climax.

MH Of course, all the conflicts are so big, so fat, so intense, that one ends up desperate. Mentally exhausted.

And how can something that has ended up being so big be properly closed?

JL Going back to the essence of the characters, which was what people fell in love with in the beginning, the characters. The war has come later.

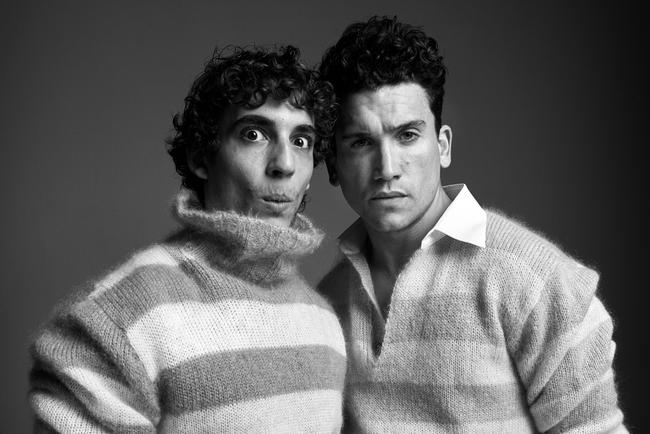

Realization: Nono Vázquez. Makeup: Lucas Margaret. Hairdresser: Sergio Snake. Photography assistant: Quique Escandel. Digital operator: Javier Torrente. Styling assistant: Martí Serra.

You can follow ICON on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or subscribe to the Newsletter here.

The daring photo session of Megan Fox and Kourtney Kardashian that causes controversy: They are accused of plagiarism

The Canary Islands add 2,327 new positives and 15 deaths from COVID-19

Spain stagnates in the fight against corruption: the country has spent a decade maintaining its levels in the Corruption Perception Index, which includes the opinion of managers and experts

The 30 best Capable Women's Briefcase: the best review on Women's Briefcase