Giving a gift in Japan is much more than giving a simple gift to someone; it is often a social obligation steeped in symbolism and tradition. From souvenirs after a trip to offerings on special occasions, all gifts must follow a series of presentation, amount and quality standards.

Giving a gift, known in Japanese as zōtō (贈答), is part of the social tradition of this country, and is therefore a very important component of Japanese culture and social interaction; a way to create good relationships between people. However, giving gifts is often more of an obligation than just a tradition. In the same way, it is also a deeply rooted custom and practically obligatory to return the gift by making a gift after receiving it, an effect known as okaeshi (お返し) in Japanese.

Among the many occasions in Japan in which it is customary –and almost obligatory– to give a gift or offer money, we can cite the following: when returning from a trip, as thanks for having received an invitation, when receiving extra payments from December and June, at New Years, at weddings, funerals, births, moving and job changes, etc. Next, we are going to see the most common occasions in which an offering is tradition, as well as norms and rules to faithfully comply with said tradition.

Table of Contentshide 1 The rules of giving and receiving gifts2 Special occasions and offering money2.1 Weddings2.2 Funerals2.3 Births2.4 Hospital visits2.5 Starting elementary school2.6 Moving2. 7 Change of city or job2.8 Arrival of summer2.9 Arrival of winter2.10 New Year2.11 Favors3 Omiyage and temiyage4 Not so traditional occasions5 Etiquette in the business world6 The importance of packagingThe rules of giving and receiving gifts

In Japan, more than in any other country, there are a series of rules to follow when choosing a gift for a specific occasion. There are some details that, due to their use and offering at other times, it is better not to give as gifts, since they can bring bad luck or simply seem inappropriate.

For example, the giving of green tea is a traditional act at funerals and other Japanese funeral services, so a pot of green tea should never be given as a gift on occasions other than mourning. Another even clearer example is combs (kushi (櫛) in Japanese), an object that should never be given as a gift, since its pronunciation is the same as the word for suffering (ku) and death (shi). Naturally, this similarity in pronunciation means that the comb is seen as an object that can bring misfortune, pain and bad luck in general.

In addition, the number of gifts that are given must also be taken into account, since certain numbers are traditionally considered to bring bad luck. For example, one of the numbers best known for its bad luck is four, considered a bad omen because its pronunciation (四, shi) once again resembles that of death (死, shi). For this reason, we can never give someone four gifts or give them a gift that consists of four parts, etc. Another taboo when it comes to giving gifts is offering clothes that touch the skin to older people, as it is considered something too intimate, although socks are an exception.

One of the things that most surprises a Westerner who gives a gift to a Japanese person is that he thanks him but doesn't open it immediately. This is a very Japanese tradition that can be understood as a way to avoid having to pretend when opening the gift if it does not meet expectations, thus avoiding embarrassment for both the recipient and the giver. This etiquette rule is highly respected on formal occasions. Among friends, however, it is more and more typical to ask when receiving the gift if they are allowed to open it at that very moment, knowing that the answer will usually be "yes, of course!".

When a gift is offered, it is customary for the recipient to initially refuse to accept it up to three times! This is a very Japanese way of acting, which we can see even when offering to try food, offering to help, etc. However, despite these supposed refusals, the recipient always accepts the gift, but not before giving these polite refusals, since all this is governed by a cultural rule. There are many occasions when a Japanese will deny an offer right off the bat, even though deep down he wants to accept it.

When giving a gift, you should also bow politely and deliver the gift with both hands, palms up. The recipient will receive it in the same way, with both hands and a polite bow (much like business cards are received).

Special occasions and offering money

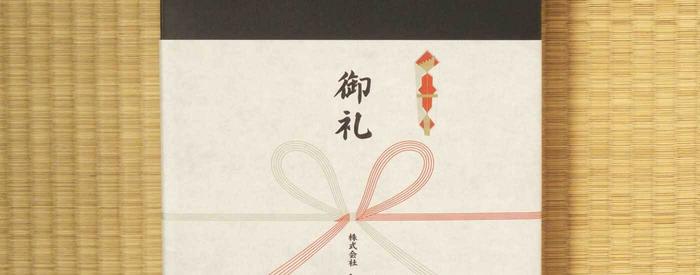

Giving money inside a special envelope called noshibukuro (のし袋) is a deeply rooted custom on certain occasions in Japanese social life. To close the envelope, a special string is used that can be tied in a knot or a bow and can have different colors depending on the occasion. Naturally, it is important to remember the bad omen of the number four, so that we can never offer money figures that contain this number.

There are many occasions in which it is common to offer money, but also other types of gifts and special details. The most peculiar characteristic of the money offering is, above all, the specific use of various types of envelope, each specific for a specific occasion. Next, we are going to see some of these more special occasions.

Weddings

At a wedding (gokekkon iwai) it is common to give new bills, that are not wrinkled or used and that are clean. This symbolizes the new life that the married couple will begin.

In this case, the envelope string should be either red and white or gold and silver and tied in a knot. Naturally, the amount will depend on the relationship you have with the couple, but normally it is between 30 and 70 thousand yen (never even numbers, that is considered a bad omen).

Funerals

At a funeral (ososhiki), it is common to give used, crumpled, and old bills. This indicates that one was not prepared for that death, did not know what was going to happen and could not have organized everything.

In this case, the envelope string must be either black and white or yellow and gray and tied in a knot, whether the funeral is Buddhist or Christian. The amount is usually around 3,000 yen. Likewise, it is common for guests to also receive a detail for their visit.

A few years ago they used to be gift vouchers to spend at department stores, but over time the ideas have changed.

Births

When there is a birth (go-shussan iwai) it is customary to give away toys, clothes or even money a week after the baby is born. In the case of sending money, it must be delivered in a red and white string envelope tied with a bow.

Of course, one has to make sure that the baby is healthy before sending his offering, because if the baby has some kind of problem, sending gifts can be seen as a symbol of bad luck. Normally, the new parents return the detail in the form of a typical square wooden cup with the name of the baby inscribed on it.

Hospital visits

When we go to see a relative or friend at the hospital (omimai) it is common to offer bouquets of cut flowers. Likewise, it is also well seen to offer books and reading to make the stay in the hospital less stressful.

However, neither the camellias nor the plants are good offerings to a patient, since the way in which the flowers of a camellia fall reminds the Japanese of death and in the same way, the roots of the plants symbolize a death. long stay in hospital. These are two ideas that must be avoided whenever we visit a Japanese hospital.

Starting Elementary School

With the beginning of elementary school (go-nyugaki iwai) it is a tradition to give about two thousand yen worth of books and school supplies when a friend's or neighbor's child walks in in elementary school. As is customary, the child's family will return the favor by giving a thank you card with red and white string and tied with a bow, and most commonly a serving of sekiban, rice cooked with red beans.

Moving

In Japan, when someone moves into a new apartment, it is a tradition (and almost a social obligation) to introduce themselves to their new neighbors (hikkoshi aisatsu). For this, it is customary to offer a small detail door by door. And it is that moving to Japan implies becoming part of a new community. And that is a very important concept in the Japanese social code.

This tradition is a way to tie ties with the community, to be part of it, to create bonds of trust, security, etc. It is also a way to apologize for the inconvenience caused to the neighbors during the move.

It should be noted that in most department stores one can find a specific section of small details to give to new neighbors. Among the most common gifts are sets of towels, kitchen towels and packs of detergents or household cleaners, that is, items related to the home and especially household cleaning.

It's official, our article has been published! If you want to read about how to treat elderly Multiple Myeloma pati… https://t.co/2RcTtbszRF

— Arthur B. Wed May 06 06:18:10 +0000 2020

So, it is not an expensive gift, but simply a detail to introduce ourselves to the neighbors and make ourselves known. This is important, since giving an expensive gift would have the opposite effect and would only make our neighbors feel indebted.

As usual, it is usually delivered with the traditional sheet-envelope with a bow on which the concept of the gift appears (in this case, due to moving) and the name.

While in the towns, where the sense of community is still very close, this tradition is still alive, the truth is that especially in the cities and among young people, where the neighbors know each other and interact less, the The hikkoshi aisatsu tradition is unfortunately being lost.

Change of city or job

When a stage in a person's life comes to an end, such as a change of residence or a change of job (osenbetsu), it is normal for organize farewell parties and have the people closest to you offer small gifts or farewell envelopes with a red and white string tied in a knot.

In the same way, it is common for said detail to be returned after the march in the form of a postcard and thanks.

Arrival of Summer

With the arrival of summer, malls across the country are preparing for the season of ochūgen, (お中元) the gift of summer. This is a gift that we give to friends, family and colleagues in mid-July, theoretically once the extra pay has been received.

The purpose of the gift is to thank you for your help during the first half of the year. And formally ask them to continue helping us during the second half of the year. This is the Japanese expression yoroshiku onegaishimasu that is widely used in Japan. Thus, the ochūgen is not just a gift, it is not just an expense. It is a show of appreciation for the other person.

Given the Japanese appreciation for food and drink, ochūgen usually consists of seasonal food, cookies and sweets, beers, spirits and various alcohols, or food of all kinds (packaged or fresh). However, there are no written rules and almost everything will be welcome. They usually cost between 3,000 and 5,000 yen.

The norm says that the ochūgen should be given to relatives, close family acquaintances (in the case of arranged marriages or omiai, special mention to the person who put the two parties in contact), to our family doctor, to our children's teachers, our boss and our most loyal customers, if we have them. Naturally, at present everything depends on the relationship we have with each of these people and if we feel that we should thank them for their collaboration during the first half of the year or not.

Traditionally, the ochūgen is usually wrapped in the traditional wrapping paper called noshigami, used in the vast majority of ceremony or tradition gifts in Japan, which is basically a white wrapper with a bow in the center. In the noshigami packaging, the reason for the gift (in this case, 御中元) usually appears at the top of the bow and the name of the person giving the gift (although this is optional) at the bottom.

Apparently, the ochūgen has Taoist and Buddhist roots, two religions whose traditions and celebrations were mixed to shape the current traditions. For example, according to the lunar calendar, July 15 was a ceremonial day for Taoism and the date of the Obon festival of the dead for Buddhism, which is why it was on this date that gifts were first presented in honor of the dead. dead and then gifts began to be given to neighbors and family friends and finally as a thank you to all the people with whom we shared our time.

If we walk through the basement or depachika floor of Japanese department stores during the summer months and also in supermarkets and konbini convenience stores we will see a thousand and one examples of ochūgen: precious and decorated gift boxes that can contain basically anything , from the simplest and cheapest (powdered coffee or beer cans) to the most exotic and expensive (such as Kumamoto melons).

Of course, whatever is in the box, it will always be perfectly arranged and arranged so that it really enters through the view. Currently, when the time comes, there are many department stores that organize a special section full of perfect gifts for oseibo and ochūgen. In addition, they facilitate the packaging and shipping of the same, so making this type of gift is becoming easier.

The tradition of ochūgen is still very much alive among middle-aged people (I myself received ochūgen from several of my students during my stay in Japan), although it seems to be losing popularity among the young. However, thanks to catalog shopping services with thousands of products like Japan Post's, the ochūgen tradition seems to be revitalizing. Now we no longer have to go to the store, look and re-look or be advised by the clerk on duty, but we just have to review the specific catalog of ochūgen products from Japan Post or e-commerce pages such as Rakuten and make the purchase. order. Easier impossible.

Let's see if the young generations keep this beautiful tradition alive.

Arrival of winter

In the same way that with the first extra pay of the year in July the ochūgen or gift of summer is made, with the second extra pay of December the oseibo or gift of winter. At that time it is a tradition to give some kind of gift to work colleagues, friends, neighbors and relatives to thank them for their kindness and help during the year.

As with the ochūgen, the oseibo's gift is usually something "consumable", such as seasonal food, canned food, quality food (best quality meats, fresh seafood, exceptional fruits), sweets and cakes , beer, tea, various liquors (especially sake) or household, kitchen and cleaning products.

The oseibo usually costs between 3,000 and 5,000 yen, depending on the relationship we have with the recipient, although we must bear in mind that it is more important than the ochūgen, so we will have to remember what gift we gave and how much we spent in summer when deciding the winter gift.

In addition, it is traditionally wrapped with the traditional noshi gift paper in which we must write the reason for the gift (in this case, oseibo) at the top and our name at the bottom.

Today, many see the oseibo as a social obligation rather than a way of saying thanks and, like many other traditions, it seems that the oseibo is losing steam among young people, especially among the urban population who prefer to exchange Christmas gifts, something more personal and private and less corseted than the oseibo.

Still, today, in the depachika or underground floors of department stores we can find a selection of Christmas gifts along with a selection of perfect gifts for the oseibo, whose packaging and shipping they facilitate themselves, making it very easy buying these gifts and maintaining this tradition. In addition, catalogs and online stores have also become popular, which with just one click make life easier for us when buying and sending oseibo.

If you do business with or have a direct relationship with the Japanese, it might be a good idea to maintain the oseibo tradition to strengthen relationships. Although of course, with so many facilities to buy and send it, with beautiful packaging, catalogs and so on, the question arises as to whether when we receive an oseibo we are really receiving a "personal" gift.

New Year

January 1 (Oshogatsu) is the busiest day for postmen across Japan. The reason is the mass mailing of New Year's cards (nengajō), which family, friends, acquaintances, and work colleagues send to each other every year.

These cards have both traditional designs, which show the animal of the coming year, and modern, which use family photos showing children, photos of an exotic trip, pets, etc. All cards marked as nengajō (年賀状) are stored at post offices and are not distributed until January 1 morning.

Another round of New Year's card mailings takes place just after a few days, when those who have received a card from someone they haven't sent one to, have the chance to fix that social error by sending a card.

In addition, children receive an envelope with a certain amount of cash (called otoshidama, お年玉) from their adult family and friends, to start the year off on the right foot. It does not have to be a large amount of money, nor is it necessary to give it to all those children close to our house; it will only be necessary to deliver it to those children with whom you have a closer relationship.

Favors

In Japanese culture, asking for a favor (meishi gawari) is one of the most complicated things there is. For this reason, when someone is forced to do so, they will have to give the person who will do them the favor a gift in advance, the meaning of which is to ask their forgiveness for the trouble caused and to thank them for having listened to them.

It is interesting to note that this detail is usually something quite expensive and elegant.

Omiyage and Temiyage

Omiyage (お土産) could easily be translated as souvenir. When a Japanese travels, he usually buys small items in the form of souvenirs for family, neighbors, friends and work colleagues.

This tradition, which can almost be seen as an obligation, can be understood within the labor framework of Japan: taking vacations is almost an offense, since it supposes an abandonment of the company and the human team that is in it, so that a gift in return can help assuage the guilt that is felt.

At work, it is usually enough to deliver sweets or fruits typical of the region that has been visited. Something that is not very complicated, honestly, since from department stores to small shops near train stations they have a specific section for omiyage of food and drinks dedicated to the specialties of the region.

For friends and family, in addition to regional food and drinks, there is a good assortment of region-specific artisan products called meibutsu (名物). These can be lacquered wood products, typical ceramics from the area, hand-painted or Japanese paper fans, embroidered products or products made with hand-painted fabrics or even netsuke (根付), a small sculpture made of ivory that serves to ensure the obi belt

Omiyage should not be confused with temiyage (手土産), which is the name given to a small gift that is given to another person to thank them for an invitation or something that we take when visiting a friend or family member. Seasonal fruit, regional cookies and typical sweets are good examples of temiyage.

Not-So-Traditional Occasions

Giving gifts for birthdays or Christmas is not part of the most orthodox Japanese tradition, but due to the importation of Western practices, today's Japanese are They are accustomed to giving gifts also on these very important dates. It must also be remembered that in the past the birthday of all Japanese was commonly celebrated on New Year. Currently, however, the Western tradition has prevailed over the Japanese practice and it is increasingly common to give and receive gifts on birthdays and even at Christmas.

Similarly, two other less traditional dates that are gaining more importance every day among young people are Valentine's Day (February 14) and White Day (March 14). For Valentine's, it's common for girls to give boys chocolate, while boys return the gift a month later for White Day. It is important to emphasize that girls not only give chocolate to their partner or special someone, but also to friends, relatives, work colleagues, etc.

Etiquette in the business world

As previously mentioned, in Japan the exchange of gifts at work is extremely important: the oseibo, the ochūgen and the omiyage are an essential part of the Japanese working life.

In general terms, we could say that the best time to offer a gift is at the end of the business visit, since this is a way of thanking the recipient for the attention they have provided. It is also important to remember that when giving a gift to a specific person it is polite to do so in private. It is also necessary to take into account the fixed hierarchy in Japanese offices, so that giving the same gift item to two people of different rank is seen as disrespectful towards the superior.

When giving a gift with both hands and palms up, it is important to comment that the gift is simply a detail, an unimportant thing (in Japanese, tsumaranai mono), even if it is not true. This is the way of expressing that the relationship is more important than any other object, regardless of the monetary cost.

In businesses more than anywhere else, gifts are always opened in private, not immediately before the person who made the offer. As already mentioned, this prevents disappointment from being noticed if the gift does not meet the expected standards and avoids embarrassment. Also, when giving gifts to different people of different positions, opening gifts in private prevents comparisons. Just like outside the office, also with business gifts it is customary to refuse to accept it at least a couple of times before finally accepting and thanking it and it is also customary to give another in return, as a polite way of thanks and respect.

In the business world, among the most valued objects as gifts are international brand products, imported liquors, haute cuisine foods, expensive pens and pens, etc. Among the gifts that should never be given are, as we have already mentioned, camellias –associated with death– and plants –associated with illness. Likewise, it is worth remembering the bad omen of the number four and the importance of red at funerals, so that if you want to deliver a card or envelope, it can never be red.

The importance of wrapping

Given the importance Japanese people place on presentation and visual forms, the wrapping of a gift is almost more important than the object itself, and is part of the gift itself. gift, so it is a detail to take care of. There are many books dedicated to explaining and illustrating different gift wrapping techniques and specific sections of department stores always try to innovate and change the wrapping technique to surprise the customer.

The traditional Japanese wrapper, however, is furoshiki< (風呂敷き), a beautiful fabric with Japanese motifs that can be used to wrap a gift or to simply transport material, like a bag.

Post originally published on June 9, 2006. Last updated: May 13, 2020

Without mining or Portezuelo, a company that produces wine is born in Malargüe

Goodbye to Carlos Marín: this is the heritage and fortune left by the singer of Il Divo

Record of women affiliated with Social Security, but temporary and with low salaries

Ceviche to Recoleta and croissants for officials: the bet of the workers of Villa 31 to sell outside the neighborhood